The Friendship Nine consisted of students from Friendship Junior College. These students are best known for their historic one-mile walk from Friendship Junior College to McCrory’s Variety Store on January 31, 1961. They walked into the front door of McCrory’s expecting adversity and as they sat at the segregated lunch counter, they received just that. They were arrested moments later.

The Friendship Nine may not have been the first Civil Rights protestors in South Carolina, but what made their protest unique is the movement it created: Jail, No Bail. “Jail, No Bail” requires protestors to be arrested and then refuse to pay or accept bail under any circumstances. The Friendship 9 chose to serve full sentences. Learning by their example, many protestors throughout the south began to replicate their efforts by participating in the “Jail, No Bail” movement themselves.

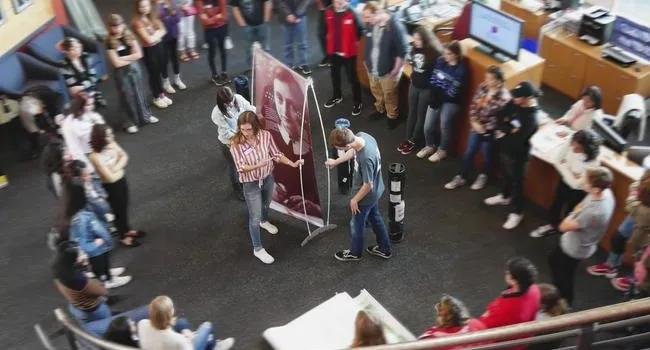

The Friendship Nine’s significant role in the Civil Rights movement in Rock Hill, South Carolina was not recognized until the late 1900’s. In 1997, McCrory’s closed down. This created a concern that the lunch counter, and a part of history, might be lost. Being that is was also the turn of the century, The Culture and Heritage Museum Board of Rock Hill were trying to decide what was the biggest thing that happened in the previous century. After several interviews and hours and days of research, they came to the conclusion that the most significant thing that happened in York County and Rock Hill was the Friendship nine and the beginning of the Civil Rights Era in South Carolina. In 2007, historical markers were placed on Main Street in Rock Hill that explained who The Friendship 9 was. In 2016, The Freedom Walkway was completed. The Freedom Walkway is a mural in downtown Rock Hill that has been dedicated to the Friendship 9 and other local heroes. Among The Friendship 9 is Rock Hill native David Williamson Jr.

“I’m back in Rock Hill,” Williamson explains, “I lived in New Jersey for twenty years, and raised a family and never told my family about it, my children anyway. My daughter came down here and went to Winthrop in 1981 and she saw an article in the paper. She saw my name and called me up, and she laid me out, why I didn’t tell her!” Humbly, Williamson continues, “I said, well, one thing, when I left Rock Hill, they called me a jailbird. And I said, you never brag about nothing you do. If you brag about it, that means you did it so you have something to brag about.”

He explains his motivation for participating in the protest. “Everything we did was not for us…if we benefited, fine, but if we didn’t, we wanted the next generation to. And just like my parents, we did it to make things better for them before they left. Because if my father was living now, he’d be surprised that they got my name on a chair and that they’re gonna put my name on a wall on Main Street. When I was 12 years old, they brought me down here and I started shining shoes and cleaning up the barber shop on Main Street.”