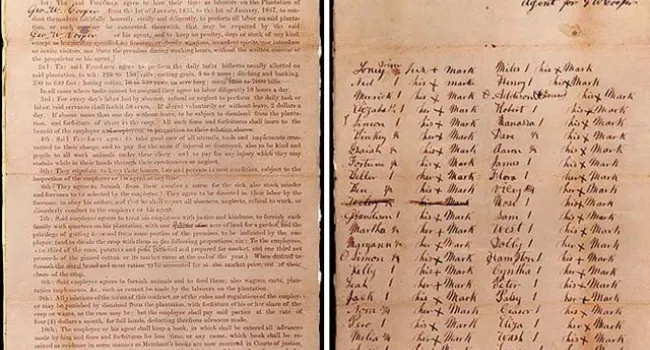

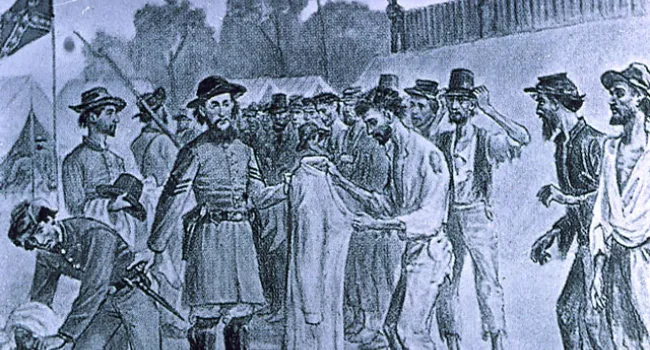

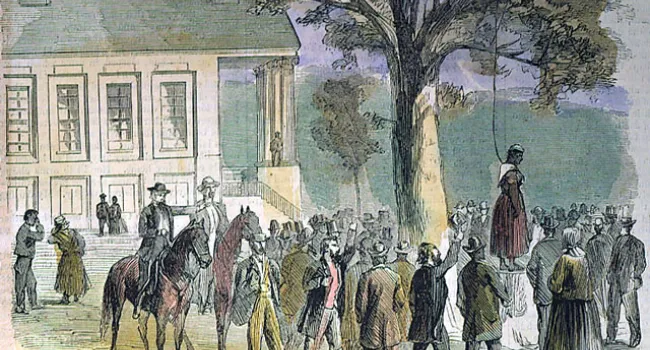

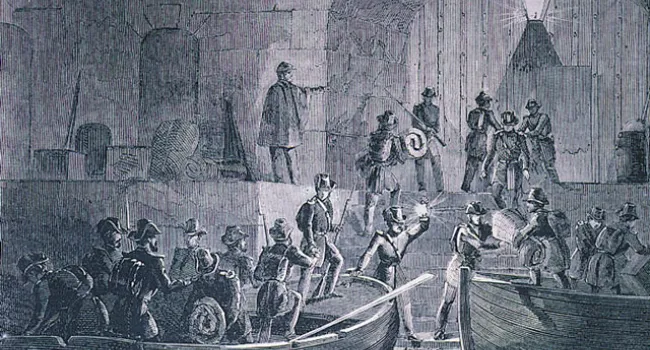

The Emancipation Proclamation has often been misunderstood, even by those who admire it. Abraham Lincoln disliked the system of slavery, but he made it clear from the beginning that the war effort was to preserve the Union. He reprimanded General John C. Fremont for declaring an end to slavery in Missouri, and rescinded Fremont's order in August 1861. As late as August 1862, Lincoln explained to the "New York Tribune" that, "If I could save the Union without freeing any slaves, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it." But as long as the North avoided linking the war directly with slavery, it also risked a successful appeal by the Confederacy for recognition by England of its independence. By the end of 1862, Lincoln realized that ending slavery had the potential of raising northern morale, and of putting the federal cause on a higher moral plane. He waited until a military victory could support his proclamation. In the horrible carnage of the Battle of Antietam Creek, near the tiny village of Sharpsburg, Maryland, he found his opportunity. Five days after the withdrawal of Lee's troops back across the Potomac, Lincoln, on September 22, 1862, called on the South to lay down their arms, return to the Union, or accept the abolition of slavery. When he received no response, on January 1, 1863, he proclaimed all slaves in states still in rebellion to be "forever free." The proclamation did not free any slaves in the four border states still within the Union. But to African-Americans in South Carolina, January 1 became the symbolic day of celebration of their freedom. On Port Royal Island, where former slaves had endured a status of "contrabands" that regarded them as neither slave nor free, Emancipation Day was indeed a day of celebration. The volunteers of the First South Carolina Regiment in this engraving have been addressed by the "color sergeant" who had just received the stars and stripes under the "Emancipation Oak" on Smith's plantation. From "Harper's Weekly," January 1, 1863.

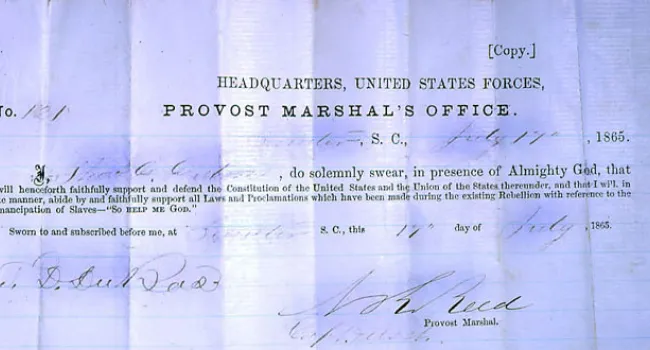

Courtesy of the South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

Standards

- 4.4.P Explain how emancipation was achieved as a result of civic participation.

- This indicator was designed to encourage inquiry into the continuities and changes of the experiences of marginalized groups such as African Americans, Native Americans and women, as the U.S. expanded westward and grappled with the development of new states.

- 8.3.CC Analyze debates and efforts to recognize the natural rights of marginalized groups during the period of expansion and sectionalism.