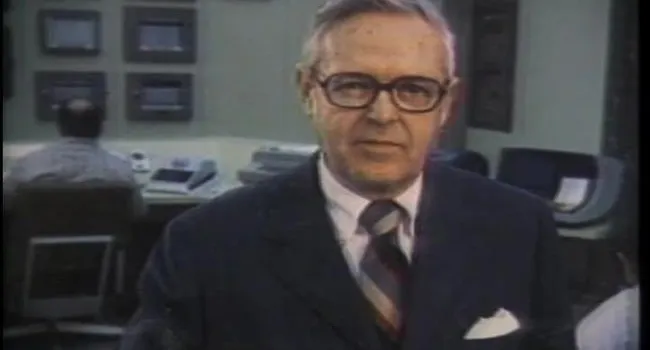

1909 - 1982

Herman Lay's first business enterprise was selling Pepsi-Colas from a makeshift stand in his family's front yard in Greenville. He was 11 years old. He was successful, charging a nickel a bottle while the city baseball park across the street was charging a dime. Ironically, just 45 years later, he was selling Pepsi-Colas again, but this time as chairman of PepsiCo, Inc., a multibillion-dollar conglomerate that he helped create.

As a young man searching for a career during the Great Depression, he suffered some lean years, but no hard-luck lessons were lost on Lay. He finally found his niche in the snack foods industry and literally wrote his own success story, making his name and Lay's Potato Chips synonymous with snack foods throughout the South and later the world, and becoming one of the nation's most successful entrepreneurs.

Herman Warden Lay was born June 3, 1909, in Charlotte, N.C., the son of Jesse N. and Bertha Erman Parr Lay. His father was reared on a farm and successfully sold farm machinery during an era when most farmers were still satisfied with their horses and mules.

The family moved to Blackville in South Carolina and later to Greenville, where Lay first began honing his talents for selling and entrepreneurship. His early Pepsi-Cola venture grew so rapidly that he opened a bank account, bought a bicycle, hired other boys to operate his drink stand, and started delivering newspapers.

When the ballpark moved from his neighborhood, he went with it, selling peanuts during the games. Ever creative, his approach was unique. His spiel was, "Hey, get your nicely roasted, nicely toasted California sun-dried, long-eared, double-jointed peanuts! Five a bag!" He soon became one of the park's top salesmen.

Lay was a good athlete, and his ballpark sales experience and proximity to professional baseball made him dream of one day becoming a baseball player himself. He attended Greenville High School and graduated in 1926, lettering in baseball, basketball, and track.

He received an athletic scholarship to attend Furman University, where he played baseball and basketball, but left school after two years to pursue a sales career.

The 1928 Democratic Convention in Houston beckoned. He and a friend invested $100 in ice cream they planned to sell along the convention parade route. But their investment melted away when the parade was rerouted at the last minute, leaving them and their ice cream on a deserted street.

Undaunted, Lay went to work in the Midwestern wheat harvest and on to Washington state to work as a lumberjack. He returned to South Carolina, and from 1930 to 1932, he held a variety of jobs, such as salesman in a novelty jewelry store in Greenville, trainee for a farm machinery company (he didn't have the farm background his father did), and employee of Sunshine Biscuit Co. in Atlanta. None promised the future Lay was seeking, however.

At 24 years of age, he was the owner of a four-year-old Model-A Ford, had a few dollars in his pocket, and was ready to take on the world. The Great Depression made jobs scarce, but Lay was persistent. He placed classified ads, and wrote 200 letters to prospective employers.

He got one response, from Barrett Potato Chip Co. in Atlanta, distributor of Gardner's Potato Chips. He interviewed for the job, but turned it down, deciding there was no future in potato chips. He once said in an interview, "I wanted to be a salesman, all right, but the idea of driving a truck from store to store selling potato chips wasn't my idea of a job."

A week later and still no job, Lay had second thoughts about the position he turned down. So back he went to the Barrett Co., only to learn that the job had been filled. However, he was employed as an extra salesman, selling and making deliveries. He liked the work and approached it with a brand of enthusiasm that became something of a trademark for Herman Lay.

That same year, Lay was named distributor in Barrett's Nashville office. He recalled in an interview, "I would get a weekly allotment of potato chips and a cash allowance. There was no salary, just the advance against whatever commissions I earned on sales. The territory would be in northern Tennessee and southern Kentucky, including the city of Nashville."

Now he had a job and his own territory. "I kept telling myself it was my territory and my business. This sense of independence kept me working. Out in the morning and on the road, all day, half the night, sleep where I was, and go again."

Driving his Model-A, he sold potato chips to road stands, grocery stores, filling stations, soda shops, and anywhere else customers might buy chips, including schools and hospitals.

By year's end, his territory had expanded and his profits had risen. In 1933, he added a salesman. Three years later, he had 25 employees and had to move to a larger warehouse.

Meanwhile, in 1935, he married Amelia "Mimi" Harper of Clarksville, Tenn., and they made their home in Nashville. They would become the parents of four children: Linda Lay Chambless, who died of Hodgkin's disease at the age of 21; Susan Lay Atwell; H. Ward Lay, Jr.; and Dorothy Lay. There are nine grandchildren.

In 1938, a Barrett representative contacted Lay and offered to sell him the company's plants in Atlanta and Memphis, Tenn. The price was $60,000. Lay asked for a month to raise the money, and began looking for investors: friends, business associates, a life insurance broker, even a gas station operator. In all, he raised $5,000. Then with a $30,000 bank loan, he persuaded Barrett to take the difference in preferred stock.

The Lays moved from Nashville to Atlanta, and on October 2, 1939, "H.W. Lay Co." signs went up and the Barrett signs came down. Lay was on his way.

Lay purchased the Barrett's plant in Jacksonville, Fla., and during the next few years, established manufacturing plants in Jackson, Miss., Louisville, Ky., and Greensboro, N.C. In the 1950s, he bought two other snack food companies, increasing his product line and area.

In 1956, H.W. Lay & Co. became publicly owned. By then, it was the largest producer of potato chips and snack foods in the country, with more than 1,000 employees, manufacturing plants in eight cities, and branches or warehouses in 13 others.

Opportunity came his way again in 1961, when H.W. Lay Co. merged with Dallas-based Frito Company. By year's end, Lay became chief executive officer of Frito-Lay, Inc., and soon advanced through the ranks to become chairman as well as CEO.

The merger meant moving his family to Dallas after 20 years in Atlanta. In Dallas, the Lays bought a lot in North Dallas, hired an architect, and built what one magazine writer described as a "huge Gone with the Wind Colonial home."

As Lay was searching for an opportunity to further expand Frito-Lay's reach into a global marketplace, Pepsi-Cola was chosen as the perfect merger partner, with its 5,000 people working in 100 countries. The merger was completed in 1965, the company's new name was PepsiCo, Inc., and Lay was elected chairman of the board.

For the next several years, he averaged 30 and 35 round trips a year between his Dallas and New York offices and homes, a trip he adjusted to by usually traveling with just a briefcase. In 1971, at the age of 62, he relinquished the roles of chairman and CEO and moved into the office of chairman of the executive committee of PepsiCo. His new role required that he make only about 10 trips to New York each year. He retired from PepsiCo in 1980.

After his retirement, Lay returned to private business with his son, Ward Lay, organizing several family corporations engaged in real estate, oil and gas exploration, and the manufacturing of frozen food products under the name State Fair Foods.

Today, PepsiCo operates three divisions, Frito-Lay, Pepsi-Cola, and Tropicana. PepsiCo's annual revenue in 2000 was nearly $20.5 billion, of which Frito-Lay's revenue was $12.5 billion, or 63 percent of total revenue.

Lay once said, "What my family and I have accumulated has come about through the exercise of free enterprise. I feel I owe a lot to the community and as a result, I try to be as generous as I can."

His contributions made possible the Herman W. Lay Activities Center and the Herman Warden Lay Scholarship program at Furman University. Gifts to Furman from Lay and his estate have totaled $3.8 million.

He also served as a member and chairman of the Advisory Council to the Furman University Board of Trustees and was national co-chairman of Furman's Program of Greatness. In 1965, he was named the first Furman University Alumnus of the Year, and in 1967, Furman awarded him an honorary Doctor of Laws degree. He was made a charter member of the Furman University Hall of Fame in 1970.

He endowed chairs in business education at Southern Methodist University (Herman W. Lay Professor of Marketing) and Baylor University (the Herman W. Lay Chair of Private Enterprise). His contributions made possible the Lay Science Building at Drury College in Springfield, Mo. The college later awarded him an honorary doctoral degree.

Lay was the first chairman of the Baylor University Medical Foundation. He also served as a trustee of Baylor University and Drury College.

In 1972, Southern Methodist University named him its Entrepreneur of the Year. The Greenville Society for the Advancement of Management honored him with its Person of the Year in 1974. He received the Golden Plate Award from the American Academy of Achievement in 1975, and in 1980, Baylor University gave him the special award of Alumnus Horis Causa.

Lay served on numerous corporate boards, among them Braniff International Airways, Cornet Industries, Third National Bank of Nashville, First National Bank of Dallas, Southwestern Life Insurance Co., First International Bancshares, Inc., and Duke Power Co.

In 1969, Lay received the Horatio Alger Award from the American Schools and Colleges Association. The award honors Americans who have risen from modest beginnings to become leaders of business and government.

The Herman W. and Amelia H. Lay Family Concert Organ was given to the Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas by "Mimi" Lay Hodges in memory of her late husband. The $1.8 million instrument is one of the largest mechanical-action organs ever built for a concert hall.

The 2.2-acre Lay Ornamental Garden at the Dallas Arboretum and Botanical Gardens was designed for Mimi Lay Hodges in honor of her late husband.

Lay family members worship at the Park Cities Baptist Church, where Lay was chairman of the Building Committee.

Herman Lay died on December 6, 1982, in Baylor Hospital. He was inducted into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame in 2002.

© 2002 South Carolina Business Hall of Fame