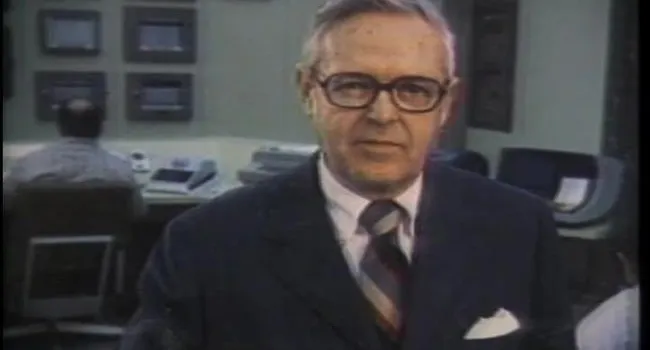

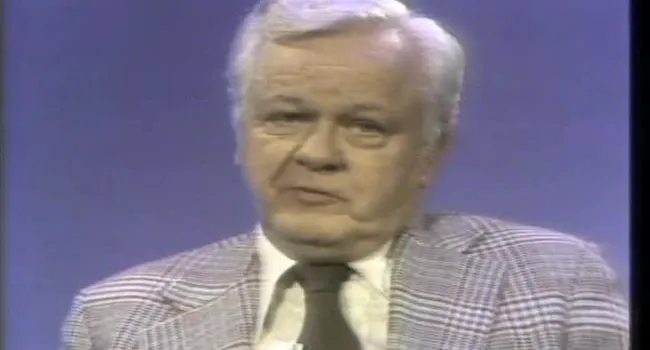

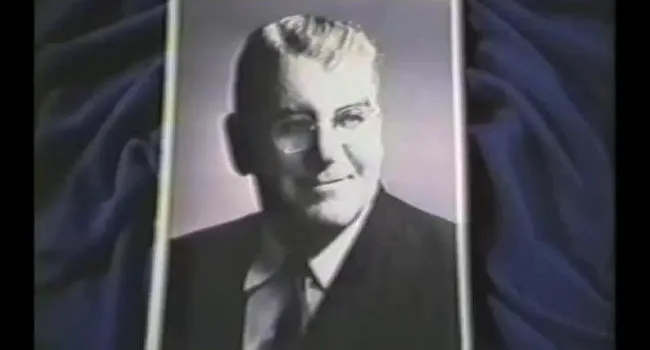

David Sloan Lewis

(1917 - 2003)

As a boy growing up in Charleston, David Lewis was fascinated by aviation. He read everything he could find about the World War I fighter planes and their romantic pilots. He built dozens of flying model airplanes and gliders. He was 10 years old when he heard that Charles Lindbergh had made the first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean. He was hooked. His career path was clear. And a rewarding career it was—for Lewis, for the United States, and for the free world.

Lewis enjoyed an illustrious 46 years as one of the nation's leading aeronautical engineers and defense industry executives. Many of the country's major weapons systems, from World War II through the Cold War to the present, including the transport aircraft of the major airlines, are part of the David Lewis legacy.

David Sloan Lewis, Jr., was born July 6, 1917, in North Augusta, the son of David S. "Dick" and Reuben Walton Lewis. The family lived in Bennettsville and Hartsville, but later moved to Charleston, where Dave, sister Lucy, and brother Jack were reared. Dick Lewis, an executive with Standard Oil of New Jersey, was transferred to Columbia in 1933, and Dave graduated from Columbia High in 1934.

He studied engineering at the University of South Carolina for three years and then transferred to the Georgia Institute of Technology, where he received a bachelor of science degree in aeronautical engineering in 1939.

After graduation, he joined the Glenn L. Martin Co. in Baltimore and, during World War II, worked on many new aircraft designs in the aerodynamics department, the wind tunnel group, the performance group, and the stability and control group. He remembers this as the "most difficult and rewarding work in the aerodynamics department."

Lewis met his future wife, Dorothy Sharpe, while both were working at the Martin Company in Baltimore. A native of Memphis, she was the daughter of Karl and Gladys Sharpe. Dorothy and Dave were married on December 20, 1941, and became the parents of four children—Susan Winslow of Mount Pleasant; David S. Lewis III of Moorestown, New Jersey; Robert S. Lewis of Marietta, Georgia; and Andrew F. Lewis of Gainesville, Georgia.

In 1946, Lewis joined the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation. in St. Louis as chief of aerodynamics and was part of a team that worked on such aircraft as the FH-1 Phantom, the Navy's first jet aircraft; the Navy's F2H Banshee; and the F-101 for the Air Force. The company grew very quickly as the country faced the Korean War and the increasing pressure of the Cold War.

The technologies of aircraft design were becoming extremely more complex, which led to the formation of a new Advance Design Department, with Lewis at the head. With no specific requirement for any new airplane on the horizon, the group's studies led to the conclusion that the Navy would profit most if it had a true combination fighter-attack aircraft. It took two years to get a contract for the Navy F-4 Phantom II. All in all, McDonnell delivered more than 5,000 F-4s to the U.S. Navy and Air Force and the armed forces of several allied countries.

Lewis moved up in several steps, becoming a vice president of McDonnell Aircraft in 1956. He was active in the development of McDonnell's Space Division that led to the company's winning effort to develop and build the pioneering Mercury spacecraft for NASA. In July 1962, McDonnell founder and chairman J. S. McDonnell named the 45-year-old Lewis president and chief operating officer, responsible for all the company's activities.

With the Cold War winding down and the inevitable reduction in government defense spending, McDonnell turned its attention to possible mergers with manufacturers of commercial aircraft. Douglas Aircraft Corporation was in financial trouble and far behind on delivery of its DC-8 and DC-9 transport aircraft. Its banks had cut off further loans and insisted that Douglas merge with another company. In 1967, McDonnell was selected because of its financial resources and strong management.

And it was David Lewis who was named chairman of the Douglas Division and given the responsibility for getting Douglas' production transports back on schedule. During his tenure in California supervising the Douglas Division's transport aircraft production, he spent much of his time visiting airlines throughout the world that had contracts for DC-8s and DC-9s.

Meanwhile, he worked with the design and sales activity for the DC-10. With an infusion of McDonnell's money and Lewis' leadership and attention to detail, Douglas became profitable again, and Lewis returned to St. Louis.He continued to work on the sales efforts for the DC-10 and was active in McDonnell's winning the contract for the F-15 Eagle, a versatile air superiority fighter that proved deadly against Syrian MiGs in the 1982 Bekaa Valley campaign.

The biggest challenge of Dave Lewis' career came in 1970 when he resigned from McDonnell Douglas to become chairman and CEO of General Dynamics. He accepted the job on the condition that General Dynamics' headquarters be moved from New York to St. Louis.

Newspaper headlines read, "Dynamics' Gain is McDonnell's Loss" and "David Lewis Lands Top Spot and Host of Problems at GD." As it turned out, both were correct.

General Dynamics, operating at a loss when Lewis took over, gradually began to become profitable, reporting significant gains for the first quarter of 1974 compared with 1973. Less than a year later, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported that "GD wins F-16 contract." Simultaneously, the St. Louis Globe Democrat was publishing a feature story titled, "David Lewis, Jr., brought corporate giant back from financial disaster."

Under his leadership, General Dynamics' sales quadrupled while net income in 1985, when he retired, was $400 million.

During Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm, General Dynamics' products were very much in evidence. Lewis took great satisfaction in some of its major weapon and launch vehicle systems in operational service, including the Tomahawk Cruise missiles, F-16 Fighting Falcons, Trident submarines, Phalanx ship-defense gun systems, and, perhaps most of all, the M1 Abrams main battle tanks.

Of the many weapons and other systems with which Lewis was involved in his career, his favorite was the F-16. Coincidentally, Shaw Air Force Base in Sumter replaced its F-4 Phantoms with the F-16, and the South Carolina Air National Guard was the first Air Guard unit to receive the F-16 Falcons. Both Shaw and McEntire Air National Guard Station supported Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

For his work in aviation, aeronautics, and astronautics, he was the recipient of many honors, among them the Robert J. Collier Trophy for the F-16 in 1975, the Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz Award in 1981, the Daniel Guggenheim Medal in 1982, and the Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy in 1984.

Lewis served as director of Ralston Purina of St. Louis, Bank of America in San Francisco, Cessna Aircraft Company of Wichita, and the Mead Corporation of Dayton, Ohio. He also served as a member of the board of trustees of Washington University in St. Louis and the Georgia Tech Foundation. He is a fellow of the National Academy of Engineering.

David Lewis III says, "One thing about my dad's character is his assumption of responsibility, even today, for projects and the well-being of the people involved in them, whether in the design, manufacture, or use of them. I've observed over the years that he genuinely worries about not only how well these aircraft, spacecraft, and seacraft perform, but also about the lives of those who use them."

Andrew, the youngest of the four children, remembers his father best as a man who put his family and its welfare far above his own and taught them morals and values by example and deed rather than word. "He has a deep, abiding faith in God, and yet he doesn't try to force his beliefs on others."

Andrew recalls his father's buying his sister, Susan, a used British MG roadster when he probably could have better spent the money on business clothing for himself. Even though he could have afforded almost any automobile he wanted, he usually drove Ford Falcons or Dodge Darts. "My mother once sent me with him to buy a new car so that he would buy something the whole family would be happy with. He wasn't trying to be humble in his choice in cars," Andrew says. "He just wanted to be sure that there would be money available in case of future family needs."

Susan, the first-born and a teenager and college student before her father's ascendency in the defense industry, remembers that "he was just a dad like everybody else's, certainly a wonderful person and a wonderful father, but not the celebrity then that he later became."

She attended a high school reunion and became reacquainted with classmates who had since gone to work for McDonnell. "They were shocked to learn that all that time in high school I was Dave Lewis' daughter and nobody knew it! To them, he was something special. He was special to me, too, but not in exactly the same way."

In 1982, anticipating retirement, Lewis began developing a plantation near Albany, Georgia, which grew to 8,500 acres of farmland and swampland. There he and Dorothy built a home and produced peanuts, pecans, corn, and quail. According to David Lewis III, there was a constant stream of friends, in and out of hunting season. Dorothy took care of the aesthetics of the property, and his father used his engineering and business skills to get the most he could from the land.

In 1995, the plantation was sold and Dorothy and David moved to Charleston, where they now make their home. They have 12 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Lewis was inducted into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame in 2000.

© 1999 South Carolina Business Hall of Fame