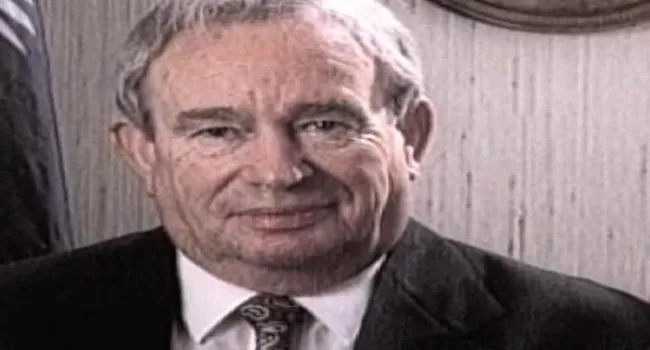

David Robert Coker (1870-1938)

David Robert Coker loved the land and the people who toiled for its bounty.

The son of Major James Lide Coker, David Coker was born on November 20, 1870 in Hartsville. He received his early schooling in Society Hill before enrolling at the University of South Carolina in 1887 at the age of sixteen. It was at the university that a keen interest in science foretold the future course of Coker’s life.

Coker became a partner in the family firm, J.L. Coker & Company, which became the largest department store between Richmond and Atlanta, after graduating. He remained involved in the company operations for the remainder of his life.

His office door was always open, especially to the farmers. As a young man working in the family business, he learned first hand about their struggles. A seed was planted that would soon grow into a whole new enterprise and a lifelong mission.

While convalescing from an illness and temporarily away from the mercantile business, he occupied much of his time with an interest he shared with his father — agriculture. He proposed that they collaborate to transform the Coker farms into one of the South’s principal experimental agencies.

It was from that labor of love that Coker’s Pedigreed Seed Company— organized in 1914 as the farm division of J. L. Coker & Company — was born. Coker became known for the development and perfection of superior strains of crops and was thought of as the “foremost breeder of seed in the entire South.” Over time, he mastered complex hybridization techniques that resulted in breeding the Hartsville long-staple cottons; varieties of oats, sorghum, and rye; corn bred specifically for Southern climatic and soil conditions; various fruits, and diverse legumes.

One of Coker’s most significant achievements was in cotton breeding. He began his experiments in 1902, at first assisting his younger brother, William C. Coker, a botanist at the University of North Carolina, then after 1904 carrying on alone. By 1914 he had developed several improved varieties of short-staple cotton. Together with the similar work of Dr. Herbert J. Webber of the United States Department of Agriculture, with whom Coker was in close touch, these improved strains greatly increased the yield and profits of Southern cotton growers. The result was a new upland cotton industry of South Carolina.

With the credo “science never fails to help any man in practical agriculture,” Coker launched efforts to re-educate the Southern farmer that were nothing short of evangelical. He sent out thousands of circulars each year and visited the cotton-growing areas of the South, preaching the gospel of better seed selection and better methods of cultivation.

In the fall of 1914, the first Coker’s Pedigreed Seed Catalogue was published. It was much more than just a sales tool. Its primary purpose was to make a case for good seed and better farming techniques. Of the 22 pages, nine, including five of the first six, were devoted to explaining methods of seed breeding. The catalogue became a personal means of communications for Coker, who offered plain spoken advice to farmers far beyond Hartsville. In fact, people from around the world flocked to the seed company farm and Coker welcomed them with his message of blending science and agriculture.By 1963, about 65 percent of the cotton grown in the Southeast, 80 percent of oats, 75 percent of flue-cured tobacco and 40 percent of hybrid corn were grown from seed produced by Coker scientists.

Coker was for many years president of the Plant Breeders Association. He served as mayor of Hartsville from 1902-1904. Shortly after the start of World War I, he was named chairman of the South Carolina Council of Defense, and later chairman of the Federal Food Administration for the state. He was also a member of the National Agricultural Commission to Europe and served as a director of the Richmond branch of the Federal Reserve Bank for two decades.

At a time when the economy of the South was staggering for a decade under the deflation following the inflation of World War I, when the price of cotton had dropped from a high point of around 42 cents per pound to 5 cents per pound and when the boll weevil was wreaking havoc on the cotton crop, banks throughout the South were failing. A. Lee M. Wiggins, then president of the Bank of Hartsville, discussed the problem with David Coker. Wiggins worried that a run on the bank might be disastrous. So the Coker family decided to make available $500,000 or more—a staggering amount during the Depression—to both the Bank of Hartsville, and its rival, the Peoples Bank of Hartsville. The family’s decision was simply stated in a letter, dated December 1, 1930, copies of which were posted in the lobbies of both banks:

“In view of banking situations in some other sections, we wish to say to you that we stand squarely behind the two banks in Hartsville and will be glad to make available to you securities up to half a million dollars or more if you should find any need of same.”

While neither bank found it necessary to take the Cokers up on their offer, they inspired confidence not only in their bank but in its rival — and ultimately in the community as well.

Coker continued his father’s tradition of being one of South Carolina’s foremost philanthropists, focusing on various social reform activities in the 1920s and 1930s. He was cited for favoring “land reform and diversification out of cotton; good roads, better schools, and greater harmony and cooperation between town and country, farm and factory.”

Interested in all phases of social welfare, particularly in education, he spent more than 20 years as a trustee of the University of South Carolina and of Coker College for Women, founded and endowed by his father. For his various accomplishments he received honorary degrees from Duke University, the University of North Carolina, the College of Charleston, and Clemson College.

He was a 2003 inductee to the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame.

Coker’s role as a champion of education was not limited to higher education. He played a significant role in bringing an agricultural education to the rural schools. “About 97 percent of the boys who attend our county schools never go to college,” he said in a letter to the editor of The State newspaper in 1913. “They get no preparation for their lives’ work besides that which comes from the home and rural schools.” When Dr. W.W. Long, head of agriculture extension work in South Carolina, spoke at Swift Creek School in late 1913, he said that he wanted to establish an agricultural education in the high schools of at least one county to show its value. But, alas, it would cost $25,000,which he didn’t have. Coker and Bright Williamson of Darlington conferred and agreed to underwrite the program in Darlington County before Long finished his speech. Long accepted on the spot.

On September 10, 1894, Coker married Jessie Ruth Richardson of Timmonsville, South Carolina, who died in 1913. They had five children who survived early childhood: Katherine, Hannah, Eleanor, Robert and Samuel. Their first child, Miriam, died at age four. His second wife, whom he married in 1915, was Margaret May Roper. They had three children: Martha, Mary, and Carolyn.

Coker’s love of botany was not lost on his family. His daughter Mary fondly remembers her father sending her out each morning to check the rain gauge or to check the temperature. He and his wife, Miss May, founded Kalmia Gardens in Hartsville, “to make it a beautiful garden as well as a botanist’s laboratory.” Much to the delight of Mr. D.R. and Miss May, Kalmia Gardens soon became a local attraction.

Coker was in ill health for some years before his death, which resulted from coronary thrombosis. He died November 28, 1938, at his home in Hartsville and was buried in the cemetery of the First Baptist Church.

Known as an agribusiness man and social reformer, David R. Coker sought over his long career to improve the profits of agriculture and lift “the level of...rural civilization.”

In October 1965, the original experimental farm was designated a national historic landmark. The dedicatory plaque reads, in part, “In 1902, in the field directly across from this marker, David R. Coker began the first successful commercial cotton improvement program in the United States based on scientific breeding. …Mr. Coker’s inspiring example of selfless devotion to the welfare of Southern farmers resulted in his becoming widely acclaimed as the South’s foremost agricultural statesman.”

His legacy lives on today in South Carolina and the South.

He was inducted into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame in 2003.

© 2003 South Carolina Business Hall of Fame