"I think the Holocaust happened because someone said, 'You're different, you don't belong.' " —High School Student

"When our children were young, they always used to ask how come people have grandfathers and grandmothers and we don't. So we explained to them our experiences and they understood."—Pincus and Renee Kohlender, Charleston Concentration Camp Survivors

The roots of anti-Semitism, prejudice against Jews, go back to ancient times. Throughout history, the seeds of misunderstanding can be traced to the position of the Jews as a minority religious group. Often, in ancient times, when government officials felt their authority threatened, they found a convenient scapegoat in the Jews. Belief in one God, monotheism, and refusal to accept the dominant religion set the Jews apart from others.

Romans Persecute Christians

The Romans conquered Jerusalem, center of the Jewish homeland, in 63 B. C. During the early period of Roman rule, Jews were allowed to practice their religion freely. At that time, the first targets of Roman persecution were Christians, considered by the Romans to be heretics or believers in an unacceptable faith. However, once Christianity took hold and spread throughout the empire, Judaism became the target of Roman authorities.

Christianity Becomes State Religion

When Constantine the Great, in the early fourth century, made Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire, religious conformity became government policy as well as Church doctrine. Christianity teaches love and brotherhood, but not all early Christians practiced these teachings. Some wanted to convert all non-believers. Jews had their own religion. They did not want to become Christians. The more the Jews remained true to their faith, the harder some worked to convert them. When Jews clung to their religion, distrust and anger grew. The Church demanded the conversion of the Jews because it insisted that Christianity be the only true religion. The power of the state was used to make Jews outcasts when they refused to give up their faith. They were denied citizenship and its rights.

By the end of the fourth century, Jews had been stamped with one of the most damaging myths they would face. For many Christians they had become the Christ-killers, blamed for the death of Jesus. While the actual crucifixion of Jesus was carried out by the Romans, responsibility for the death of Jesus was then placed on the Jews.

Religious Minorities Harshly Treated in Middle Ages

In Europe, during the Middle Ages from 500 A.D. to about 1450 A.D., all religious non-conformists were harshly treated by ruling authorities. Heresy, holding an opinion contrary to Church doctrine, was a crime punishable by death. Jews were seen as a threat to established religion. As the most conspicuous non-conforming group, they were attacked. At times it was easy for ruthless leaders to convince their largely uneducated followers that all non-believers must be killed. Sometimes the leaders of the Church led the persecutions. At other times, the Pope and bishops protected the Jews.

New Laws Set Jews Apart

The Justinian Code, compiled by scholars for the Emperor Justinian, 527-565 A.D., excluded Jews from all public places, prohibited Jews from giving evidence in lawsuits in which Christians took part, and forbade the reading of the Bible in Hebrew. Only Greek or Latin were allowed. Church Council edicts forbade marriage between Christians and Jews and outlawed the conversion of Christians to Judaism in 533. In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council stamped the Jews as a people apart with its decree that Jews were to wear special clothes and markings to distinguish them from Christians.

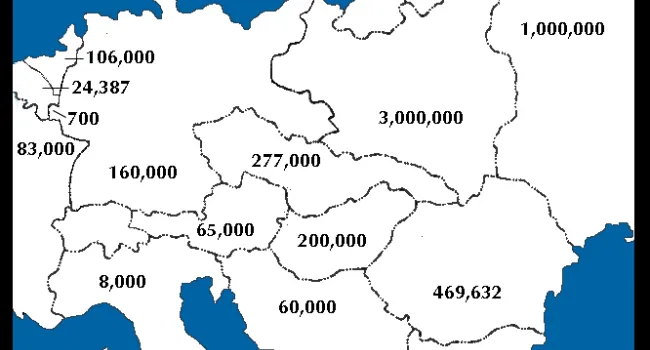

The Crusades, which began in 1096, resulted in increased persecution of Jews. Religious fervor reached a fever pitch as the Crusaders made their way across Europe towards the Holy Land. Although anger was originally focused on the Muslims controlling Palestine, some of this intense feeling was redirected toward the European Jewish communities through which the Crusaders passed. Massacres of Jews occurred in many cities en route to Jerusalem. In the seven-month period from January to July 1096, approximately one fourth to one third of the Jewish population in Germany and France, around 12,000 people, were killed. The persecutions of this period caused many Jews to leave western Europe for the relative safety of central and eastern Europe.

The Council of Basel (1431-43) established the concept of physical separation in cities with ghettos. It decreed that Jews were to live in separate quarters, isolated from Christians except for reasons of business. Jews were not allowed to go to universities. Attendance for them at Christian church sermons was required.

Many Occupations Closed to Jews

In western and southern Europe, Jews could not become farmers because they were forbidden to own land. Gradually more and more occupations were closed to them. Commerce guilds were also closed. There were only a few ways for Jews to make a living. Since Christians believed lending money and charging interest on it, usury, was a sin, Jews were able to take on that profession. It was a job no one else wanted.

Because they filled an important need in managing money and finances in a changing economy, their role expanded over the years. Jewish moneylenders became the middlemen between the wealthy landowning class and the peasants. Rulers gave Jews the unpopular job of tax collecting, causing deep hostility among debt-ridden peasants. In times of economic uncertainty, dislike of the Jew as tax collector and moneylender was coupled with religious differences to make Jewish communities the targets of attacks.

Black Death Leads to Scapegoating

The Black Death, or bubonic plague, led to intense religious scapegoating in many communities in Western Europe. Between 1348 and 1350, the epidemic killed one third of Europe's population. Many people believed the plague to be God's punishment of them for their sins. For others the plague could only be explained as the work of demons. This group chose as their scapegoat people who were already unpopular in the community.

Rumors spread that the plague was caused by the Jews who had poisoned wells and food. The worst massacre of Jews in Europe before Hitler's rise to power occurred at this time. For two years, a violent wave of attacks against Jews swept over Europe. Tens of thousands were killed by their terrified neighbors despite the fact that many Jews also died of the plague.

Not only were Jews blamed for the Black Death, but they were also believed to murder Christians, especially children, to use their blood during religious ceremonies. The blood libel, as it is known, can be traced back to Norwich, England, where around 1150, a superstitious priest and an insane monk charged that the murder of a Christian boy was a part of a Jewish plot to kill Christians. Despite the fact that the boy was probably killed by an outlaw, the myth persisted. Murdering Jews was also justified by other reasons. Jews were said to desecrate churches and to be disloyal to rulers. Rulers who tried to protect the Jews were ignored or they themselves were attacked.

Expelled from Western Europe

By the end of the Middle Ages, fear and superstition had created a deep rift between Jews and Christians. As European peoples began to think of themselves as belonging to a nation, Jews were thought of as outsiders. They were expelled from England in 1290, from France in 1306 and 1394, and from parts of Germany in the 14th and 15th centuries. They were not legally allowed in England until the middle of the 1600s and in France until the French Revolution.

Golden Age and Inquisition in Spain

Unlike Jews in other parts of western Europe, the Jews of Spain enjoyed a Golden Age of political influence and religious tolerance from the 11th to the 14th centuries. However, in the wave of intense national excitement that followed the Spanish conquest of Granada in 1492, both Jews and Muslims were expelled from Spain. Unification of Spain had been aided by the Catholic Church which, through the Inquisition, had insisted on religious conformity. Loyalty to country became equated with absolute commitment to Christianity. From 1478 to 1765, the Church-led Inquisition burned thousands of Jews at the stake for their religious beliefs.

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation, which split Christianity into different branches in the 16th Century, did little to reduce anti-Semitism. For much of his life the Protestant Reformation leader Martin Luther expressed moderate views toward Jews. Believing the Jews would become converts to the faith, Luther urged humane treatment. However when the Jews failed to convert, he turned against them. In his booklet Of Jews and Their Lies, published four years before he died in 1546, Luther advised:

"First, their synagogues or churches should be set on fire....Secondly, their homes should likewise be broken down and destroyed....They ought be put under one roof or in a stable, like gypsies....Thirdly, they should be deprived of their prayerbooks....Fourthly, their rabbis must be forbidden under threat of death to teach anymore...."

Separate Way of Life Develops in Ghetto

Religious struggles plagued the Reformation for over 100 years as terrible wars were waged between Catholic and Protestant monarchs. Jews played no part in these struggles. They had been separated completely during the Middle Ages by Church law, which had confined the Jews to ghettos. Many ghettos were surrounded by high walls with gates guarded by Christian sentries. Jews were allowed out during the daytime for business dealings with Christian communities but had to be back at curfew. At night, and during Christian holidays, the gates were locked.

The ghettos froze the way of life for the Jews because Jews were segregated and not permitted to mix freely. They established synagogues and schools. They developed a life separate from the rest of the community.

Enlightenment and the French Revolution

In the 1700s, the Age of Faith gave way to the Age of Reason. In the period known as the Enlightenment, philosophers stressed new ideas about reason, science, progress, and the rights of individuals. Jews were allowed out of the ghetto. The French Revolution helped many western European Jews get rid of their second-class status. In 1791 an emancipation decree in France gave Jews full citizenship. In the early 1800s, the German state of Bavaria, Prussia, and other European countries passed similar orders.

Although this new spirit of equality spread, many Jews in the ghetto were not able to take their places in the outside world. They knew very little about the world outside the ghetto walls. They spoke their own language, Yiddish, and not the language of their countrymen.

The outlook of thinkers of this period shifted from a traditional way of looking at the world which stressed faith and religion to a more modern belief in reason and the scientific laws of nature. A new foundation for prejudice was laid which changed the history of anti-Semitism. Now semi-scientific reasons were used to prove the differences between Jews and non-Jews and to set them apart again in European society.

Nationalism in Germany

In the early 19th century, strong nationalistic feelings stirred the peoples of Europe. Much of this feeling was a reaction against the domination of Europe by France in the Napoleonic Era. In Germany, many thinkers and politicians looked for ways to increase political unity. Impressed by the power France had under Napoleon, they began to see solutions to German problems in a great national Germanic state.

The word anti-Semitism first appeared in 1873 in a book entitled The Victory of Judaism over Germanism by Wilhelm Marr. Marr's book marked an important change in the history of anti-Semitism. In his book Marr stated that the Jews of Germany ought to be eliminated because they were members of an alien race that could never fully be a part of German society.

Aryan Superiority

Marr's ideas were influenced by other German, French, and British thinkers who stressed differences rather than similarities among people. Some of these thinkers believed that Western European Caucasian Christians were superior to other races. Although the term Semitic refers to a group of languages not to a group of people, these men made up elaborate theories to prove the superiority of the Nordic or Aryan people of northern Europe and the inferiority of Semitic people, or Jews.

Russia and France in the Late 1800s

In other parts of Europe, anti-Semitism took different forms. In 19th century Russia, pograms, massacres of Jews by orders of the czars, occurred. In France from 1894 to 1906, the Dreyfus Case revealed the depth of anti-Semitism in that country. Captain Alfred Dreyfus, the first Jew to be appointed to the French general staff, was falsely accused of giving secret information to Germany. Although cleared of all charges, his trial brought strong anti-Jewish feelings to the surface in France.

Until the late 1800s, anti-Semites had considered Jews dangerous because of their religion. They discriminated against Jews because of their beliefs, not because of what they were. If they converted, resentment of them decreased. After 1873, Jews were thought of as a race for the first time. Being Jewish was no longer a question of belief, but of birth and blood. Jews could not change if they were a race. They were basically and deeply different from everyone else. That single idea became the cornerstone of Nazi anti-Semitism.

Standards

- 5.3 Demonstrate an understanding of the economic, political, and social effects of World War II, the Holocaust, and their aftermath (i.e., 1930–1950) on the United States and South Carolina.

- 6.1.CX Contextualize the origins and spread of major world religions and their enduring influence.

- 6.5.CE Explain the impact of nationalism on global conflicts and genocides in the 20th and 21st centuries.

- This indicator was developed to encourage inquiry into how the emergence of the Indian Ocean trade route, the Silk Road, and the power shifts between different groups happened as a result of economies, politics, population, resources, and technology.

- MWH.1.CO Compare and contrast the major political, social, and belief systems and their spatial distribution in the early modern world.

- This indicator is intended to encourage inquiry into the significant causes of World War I and the impacts of the Treaty of Versailles, including its failure to prevent future global conflicts.

- USHC.4.CC Examine the continuity and changes on the U.S. homefront surrounding World War I and World War II.